Automatic Birthright Citizenship on the Chopping Block

Commentary - Friday, January 2, 2026

By Jared Culver, Legal Analyst

The Citizenship Clause of the 14th Amendment was drafted in 1866 and ratified in 1868. It states: “All persons born or naturalized in the United States, and subject to the jurisdiction thereof, are citizens of the United States and of the State wherein they reside.”

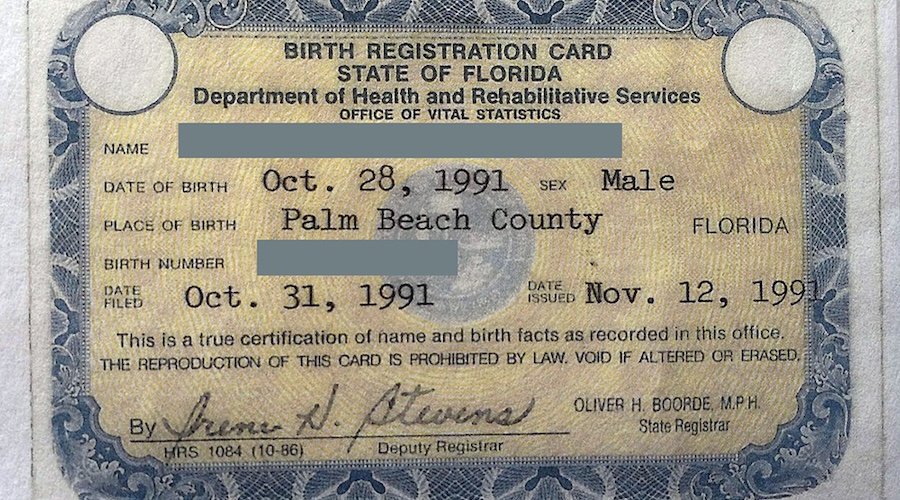

The practice of granting automatic birthright citizenship to most children born in the United States, regardless of the immigration status of their parents, has never been meaningfully reviewed by Congress or the Supreme Court. Since the mid-1900s, the Executive Branch has acted unilaterally to interpret the Citizenship Clause of the 14th Amendment expansively to include automatic citizenship for children of illegal aliens and temporary nonimmigrant aliens (including tourists, students, and temporary workers).

Legislation has been introduced in every Congress for the past three decades to reign in birthright citizenship so that it applies only to children born here to at least one parent who is a U.S. citizen or lawful permanent resident. However, Congress has never seriously debated or voted on this legislation.

On January 20, 2025, President Trump signed an executive order entitled “Protecting The Meaning And Value Of American Citizenship,” which barred the granting of citizenship to children of illegal aliens and nonimmigrant visitors. While President Trump simply used the same authority to interpret the 14th Amendment that other presidents declined to use for decades, it was acknowledged that legal challenges would ensue. Now, the Supreme Court has granted certiorari after the lower courts enjoined the President’s EO.

Many birthright citizenship advocates believe this case is a slam dunk. They are missing the boat because the case is far more contested than they admit. Namely, the Supreme Court must grapple with some crucial points:

- Automatic birthright citizenship for illegal aliens and temporary nonimmigrants contradicts current immigration law.

- Automatic birthright citizenship rewards behavior that violates Federal law.

- An all-in interpretation of the Citizenship Clause renders the phrase “subject to the jurisdiction thereof” meaningless.

- The 14th Amendment was drafted to directly overrule the Supreme Court precedent set in Dred Scott regarding former slaves and their descendants, not the children of aliens.

- The Supreme Court ruled in the 1898 case of Wong Kim Ark that children born to “permanently domiciled” aliens (today’s equivalent of Lawful Permanent Residents or LPRs) are citizens at birth, but it has never considered children born to illegal aliens or temporary visitors.

Contradiction With Current Law:

Proponents of automatic birthright citizenship for illegal aliens and temporary foreign visitors spend much of their time discussing American “common law” in the colonial period while discussing current United States statutory law very little. This despite the fact that Article I of the Constitution gives Congress sole authority to create immigration law.

Instead, they confidently point to common law practice before the ratification of the 14th Amendment. John Yoo and Robert Delaney wrote an article defending birthright citizenship from a legally originalist perspective:

“The provision effectively constitutionalized the British common-law rule of jus soli, under which, as 18th-century English jurist William Blackstone explained, "the children of aliens, born here in England, are, generally speaking, natural-born subjects, and entitled to all the privileges of such."

Similarly, Michael D. Ramsey wrote:

“In sum, the Amendment’s framers chose a phrase that was well-defined in pre-enactment law. “Subject to the jurisdiction” of a nation meant under sovereign authority, and it included everyone within sovereign territory apart from foreign sovereigns, diplomats, and armies.”

For those who didn’t waste an inordinate amount of money attending law school, “common law” refers to the unwritten judge-made law. Common law is the collection of judicial opinions/precedents governing areas like civil tort law. Thus, common law is distinct from statutory law which is written by a legislative body. Locating common law is a function of reading judicial opinions and discovering what the collection of opinions means. This is not an exact science because judges can and often do disagree about which common law precedents are relevant and what they mean. Common law is thus ad hoc and developed over time on a case-by-case basis through individualized cases. That means it is subject to change and often does change over time. On the other hand, the statutes are clearly identifiable and the question is how to interpret the words of a given statute within the context of the body of statutory law.

Importantly, for the United States common law is disparate across both the Federal government and State law. The Supreme Court in the 1938 case, Erie Railroad Co. v. Tompkins dismissed the idea of a Federal common law at all. The United States, unlike the English, created a written Constitution to avoid reliance on the esoteric idea of common law to govern. Certainly, where the Congress acts, common law cannot contradict.

While it is true that formal statutory laws governing immigration admission and naturalization were largely nonexistent in the colonial period, that is obviously not the case today. For example, 8 U.S.C. 1427 lists out requirements for aliens to be eligible to naturalize. Among other things, the law requires aliens seeking to naturalize to be already admitted as LPRs and have been residing in the United States for at least five years. Meanwhile, illegal aliens and temporary nonimmigrant visitors can create citizens unilaterally if the birthright proponents are correct.

Also, at 8 U.S.C. 1442 Congress prohibits any aliens from countries at war with the United States from naturalizing and becoming citizens, except in the careful consideration of the government. Yet, the birthright citizenship advocates would have to say application of this law would be unconstitutional with regard to their progeny. Simply enter illegally and avoid this statute’s imprimatur with regard to your children.

Current statutory law at 8 U.S.C. 1182 has a laundry list of grounds for inadmissibility that bar aliens from entering the United States at all. The inadmissible list includes: health related grounds (a)(1), criminal aliens (a)(2), terrorists (a)(3)(B), and Public Charge (a)(4), along with many others. Congress has even made it a Federal crime at 8 U.S.C. 1325 to enter the country unlawfully and made re-entry of previously deported aliens a felony at 8 U.S.C. 1326. This is difficult to square with the notion that the Constitution confers automatic citizenship on the children of aliens in violation of these provisions.

Immigration law is deeply complex, with exceptions and carve outs, but one thing is certain: proponents of automatic birthright citizenship believe none of that impacts an alien’s ability to produce citizens by birth no matter how many of those laws they violate. This presents the Court with a problem of squaring the ability of Congress to create immigration laws and an interpretation of the 14th Amendment that says colonial common law blocks the discretion of Congress to limit alien entry and citizenship. So, it could be that the Supreme Court now will recognize that current interpretations of the Citizenship Clause frustrate the goals of current statutory law.

Rewarding Violation of Law

Today’s illegal aliens and temporary nonimmigrant visa holders have no equivalent during the time when the 14th Amendment was being drafted. At the time of ratification, aliens were not defying Federal sovereignty and law when they entered. The 14th Amendment could not have been drafted to reward illegal aliens because federal law at the time didn’t recognize illegal immigration. However, the drafters did exclude foreign invaders from birthright citizenship. It seems easy enough to tie illegal aliens to illegal invaders on the premise that both are present in the United States in defiance of law and the expressed will of the people.

To read the Citizenship Clause expansively, as birthright proponents do, is to suggest the U.S. Constitution requires rewarding violation of the laws of the United States. If illegal and nonimmigrant aliens are “subject to the jurisdiction” of the United States, then they are rewarded with more power than Congress to establish the parameters of immigration law, even though Article I of the Constitution gives Congress plenary power to set immigration law. In essence, under this reading, the Citizenship Clause limits Congress’ Article I powers.

Many principles throughout America’s legal system support the basic principle that we do not reward illegal behavior as a matter of policy:

- The absurd result principle bars interpreting statutes to require absurd results (rewarding illegal entry with the power to grant citizenship qualifies as absurd).

- In the rules of evidence there is a long held principle of excluding even relevant evidence when it is acquired by illegal/illicit means called “fruit of the poisonous tree.”

- Another noteworthy example is the slayer rule barring murderers from inheriting property from their victims.

It seems absurd to assume that the drafters of the 14th Amendment intended to allow law violators to be rewarded. So, the question is: does the 14th Amendment restrict the absolute authority over immigration that Article I of the Constitution gives to Congress? The answer from the birthright supporters seems to be that it does.

Statutory Interpretation Rules Require the phrase “Subject to the Jurisdiction thereof” Mean Something

The Citizenship Clause states: “All persons born or naturalized in the United States, and subject to the jurisdiction thereof, are citizens of the United States and of the state wherein they reside.” A plain reading of this text would indicate that there are two separate requirements for citizenship:

- Being born or naturalized in the United States; and

- Being subject to the jurisdiction thereof.

This is important because another rule of statutory interpretation is the rule against surplusage. This rule states: “If possible, every word and every provision is to be given effect (verba cum effectu sunt accipienda). None should be ignored. None should needlessly be given an interpretation that causes it to duplicate another provision or to have no consequence.”

The birthright citizenship supporters suggest that “subject to the jurisdiction thereof” is intended by the drafters to mean “someone inside the geographical jurisdiction of the United States.” However, the Citizenship clause already states that the person must be born in the United States. Thus, their interpretation makes “subject to the jurisdiction thereof” to be read as a redundancy, rather than a second requirement. If the drafters thought simply being born in the United States was sufficient and/or they thought “subject to the jurisdiction” was the same as saying one must only be born in the United States, they wouldn’t have included both requirements.

In fact, the drafters of the 14th Amendment made clear during the congressional debate over the language that “subject to the jurisdiction thereof” does have a meaning distinct from “born in the United States.” They distinguished between “geographical jurisdiction,” or being within the territory subject to the laws of the land, and “political jurisdiction,” or not having any allegiance to a foreign power. They made clear during the debate that “subject to the jurisdiction thereof” referred to “political jurisdiction.”

This reading of the 14th Amendment comports with the Supreme Court’s holding in Wong Kim Ark, since an alien admitted to the United States for lawful permanent residence has given up his allegiance to his country of origin and now owes it to America, as his permanent home. The same cannot be said for illegal aliens or nonimmigrants who have no right to remain permanently in the United States.

The 14th Amendment was drafted to directly overrule the Supreme Court precedent set in Dred Scott

Students of history know that the Supreme Court’s decision in Dred Scott, which declared that descendants of slaves were not U.S. citizens, is the direct impetus for the 14th Amendment. In other words, no one can credibly claim the drafters intended to allow aliens violating statutory law to be conferred the right to produce citizens.

The first attempt to respond to Dred Scott did not take the form of a constitutional amendment. Instead, Congress passed the Civil Rights Act of 1866 that said (emphasis added):

“That all persons born in the United States and not subject to any foreign power, excluding Indians not taxed, are hereby declared to be citizens of the United States; and such citizens, of every race and color, without regard to any previous condition of slavery or involuntary servitude…”

The text of the 14th Amendment, drafted just after passage of the Civil Rights Act in 1866, was based on this legislation. The drafters of the constitutional amendment were clearly concerned about allegiance to America versus to foreign states. They also clearly drafted the amendment to ensure that former slaves would be categorized as U.S. citizens. Primary drafters, Senators Trumball and Howard, said that being subject to the jurisdiction of the United States meant owing allegiance to no one else.

Additionally, the Supreme Court discussed the Citizenship Clause in the 1873 Slaughter-House case and said, “The phrase, "subject to its jurisdiction" was intended to exclude from its operation children of ministers, consuls, and citizens or subjects of foreign States born within the United States.” This was merely dicta, but it is highly indicative of what the broad public understanding was of the 14th Amendment at the time of drafting. The Court also opined in that same opinion that the primary objective of the Citizenship Clause was to overrule Dred Scott with regard to freed slaves and their citizenship.

There was no broad national understanding that the 14th Amendment would impact future immigrant populations. Rather, the 14th Amendment arose after the Civil War to explicitly overrule the Supreme Court precedent that helped start the war. The 14th Amendment was never intended to apply to foreign nationals with allegiance to other countries.

Implications

It is impossible to overstate the importance of the Supreme Court ruling on the challenges to President Trump’s Executive Order. Estimates from the Center for Immigration Studies suggest that there were 225,000 to 250,000 births to illegal immigrants in 2023—amounting to close to 7 percent of births in the United States—and about 70,000 to temporary nonimmigrant visitors. While these numbers may seem negligible compared to the overall population, each of these new citizens will be able to sponsor parents, siblings, and extended family members through chain migration. Of the 1,172,910 foreign nationals admitted to the United States in FY2023 as LPRs, 310,610, or more than 26 percent, were admitted through chain migration categories.

Foreign nationals certainly are keenly aware of the value of this particular loophole. An odious industry has cropped up to facilitate “birth tourism,” where aliens gain admission to the United States on nonimmigrant visas for the sole purpose of giving birth to a U.S. citizen child. According to a Senate Committee on Homeland Security and Government Affairs report from 2022, the B Visa category is the most abused with regard to birth tourism. This makes sense as the B Visa is both the largest nonimmigrant category and the category with the least amount of oversight from the government.

Additionally, beginning in earnest in 2014, the illegal-alien population began to see higher proportions of women, children, and family units. For many years, much of the illegal immigration at the border consisted of single adult males from Mexico. According to Migration Policy Institute, “there were 87,000 apprehensions of Mexican family units in FY 2023—more than the total number of Mexican families encountered from 2016 through 2022.” This deliberate shift to family migration in the last decade has made the birthright citizenship policy a more acute pressure point

The Supreme Court is now set to decide whether America’s sovereign right to exclude aliens and have borders is constitutional. If the 14th Amendment requires rewarding all aliens who can gain temporary admission or violate our laws barring their admission or residence with citizenship for their children, then we basically have no immigration law at all.

Commentary - New Analysis Says H-1B Workers Driving Down Wages

Video - Rosemary Jenks: ICE/CBP status during DHS shutdown, H-1B & AI

Video - Rosemary Jenks: DHS Shutdown, H-1B visas, SAVE America Act

Video - Rosemary Jenks outlines the path to mass deportations

Video - Rosemary Jenks discusses Immigration Enforcement Options